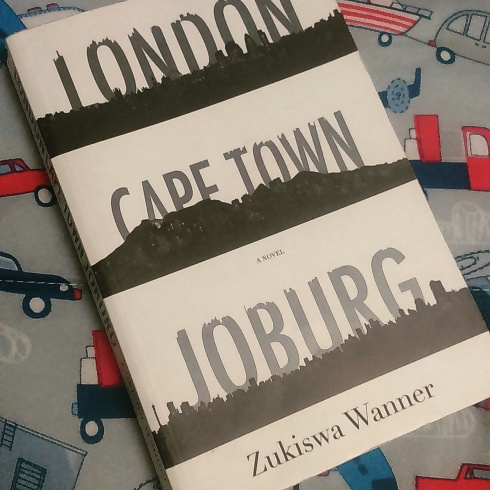

Title: London – Cape Town – Joburg

Author: Zukiswa Wanner

Publisher: Kwela Books (2014)

Pages: 337

Reviewer: Tumelo Motaung

Rating: 4/5

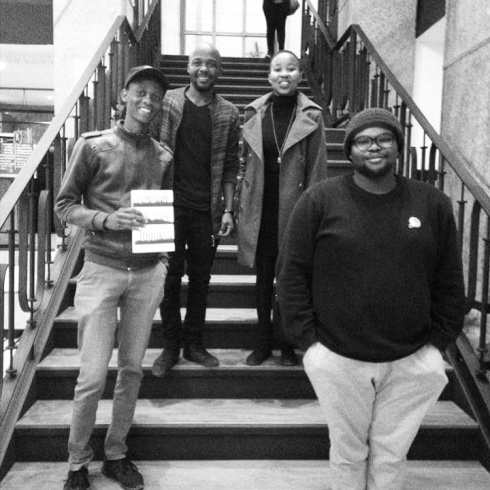

If ever there’s a book on our shelf that holds the record for Longest Actively Read Book, it is Zukiswa Wanner’s London – Cape Town – Joburg. Read over an entire month, we picked it up the week after the last @nerdafrica book club meeting, where the group had so much fun going over the topics in the book that we grew green in envy and figured that the only way to flush that was to read it.

Having owned the copy for over a year, we didn’t like the cover much, and after reading a few chapters was convinced that the storyline was a little too obvious. But also, after meeting Zuki a year ago we somewhat wanted the feeling of humble to wear off a little, not wanting the impression she left om us to cloud our judgement. This, I dare say, was a mistake on our part, because even though we weren’t enthusiastic about where the story was going, the language was so relaxed and relatable that it wasn’t easy to simply stop reading.

We would have read it in a go or two had we not started reading it during the 42nd week of our pregnancy. So instead we read it as we anxiously waited for contractions to knock down our door. And when they didn’t we read it through our hospital stay, while waiting, while healing; and just when we thought it was over, we read it through the many doctor’s appointments in the first two weeks of Atang’s life. London – Cape Town – Joburg was great company.

For the first time in our African literature journey we read what is essentially a love story that doesn’t go sour, isn’t violent, or is marred by outside interference. Germaine and Martin are in love with each other from beginning to end. I’m not too crazy about the way they meet, but Zuki assures me that the soapy-like meeting is the only biographical aspect of the entire novel, so that must count for something, right?

The novel alternates narration between Martin, who is an investment banker, and Germaine, a ceremist, and spans over a period of about sixteen years from their meeting to the death of their son, Zuko. In that time, the couple, who start off living in London, relocate to Cape Town to be close to Martin’s family, and later to Joburg live quiet, yet interesting lives that are shattered eventually by Zuko’s suicide on his fourteenth birthday.

For a 300 odd pager, Zuki manages to gracefully fill all those pages with so much life, so much love, so much truth, that one can’t help place themselves there, beside the two lovers and Zuko – when he starts keeping a journal, wondering where you were during the 2010 World Cup, or when Mbeki was outsted and Zuma came into power. We remember thinking – we also voted against the ANC so they would not get an outright majority and start pulling up their socks, go Germaine!

Because, my dear, no one does victimology like South Africans. The black people are taking our jobs according to write South Africans. And these white people can’t sell back land they never bought according to black people. We pull race cards and reverse race cards. The country will probably elect Zuma as President because he too is a victim – after all, these Mbeki people were trying to trap him and keep him down. And South Africa loves a victim negate we’re all victims, see?

What we loved most about the book is how you are always left to your minds devices, trying to figure out if Zuko is a Trevor Noah, wondering if he swims till the end, wondering how race was never an issue between Martin and Germaine when all you’ve ever felt like in these sort of relationships is a Tropical Fish (have always wanted to use that term since reading Mapule Mohulatsi‘s piece by the same title and then Doreen Baingana’s, which inspired the latter and appeared in The Obituary Tango, The Caine Prize for African Writing 2006 selection).

There is a strong female presence in the book, which – together with Tsitsi Dangaremba’s Nervous Conditions, Chimamanda Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, Yewande Omototso’s The Woman Next Door, and Farida Karodia’s is a breeze of fresh air in the long list of books we’ve read about abused, submissive women. Reading of women who rebel and fight their own battles in a sexist, misogynistic, patriarchal society (don’t mean to sound like an angry feminist here) is just wonderful.

We love the supportive relationships that develop between women in the novel. Germaine working with the Nomakanjani ladies draws a wonderful picture of the type of cooperative relationships that actually work, where every member owns a part of the business and works hard to build it up. This was important for us because having spent years struggling to find people to partner with on a children’s brand, it is also while reading this that we found our match.

As someone who has parented children who’s father’s had initially shown no interest in coparenting, you at some point wonder how you’d react when their fathers return some day and want to play happy family. Zuki here paints that picture, where Martin, already in his prime, meets his biological father. The result isn’t peachy.

When Nkagiseng, was in hospital two years back treating dog bites, a five year old boy was admitted in the same ward. He had been raped by his mother’s boyfriend. He had to pee and poop into a sac for eight months. Later on in our stay an eleven year old was also admitted. He had annal warts, and at night would cry, telling his mother to ask his transport driver who had done this to him. We were mortified. This book reminded us of these two boys, and of Taiye Selassie’s The Sex Lives of African Girls, which left us wondering who we could trust with our children.

HOME DRENCHED

We South Africans rarely

discuss the weather.

Temperature, yes, the highs and lows

of daily fluctuations, talked out in seams of

exhaled complaints. But not

the weather.

Its ordinary wisdom is never analyzed.

We are trained by the glib

sunshine

to forgive too easily, we slide into optimism

as into a well-fitting trouser.

So when the storm comes we don’t have an umbrella.

And it comes unexpectedly: we admire the mass movement

of the stately cumulus, their darkening

from cream to

bilious purple pent-up rage.

Snake-tongue lightning licking the rooftops

streets awash with revenge

cars skidding over the unstable firmament

hail hurled in furious stones .

We are terminally surprised

when we get home,

drenched. I had no idea, we say

that you were so angry.– Phillipa Yaa de Villiers